Sometimes, you know, I feel like we’re getting distracted.

Sometimes, you know, I feel like we’re getting distracted.

We focus on writing beautifully.

We pick our words with care.

We pay attention to punctuation.

We try to avoid grammar and spelling goofs.

But do we forget the basics of writing well?

The #1 reason for bad writing

In his book The Sense of Style, Steven Pinker, a cognitive psychologist and linguist, writes:

The curse of knowledge is the single best explanation I know of why good people write bad prose. It simply doesn’t occur to the writer that her readers don’t know what she knows—that they haven’t mastered the patois of her guild, can’t divine the missing steps that seem too obvious to mention, have no way to visualize a scene that to her is as clear as day.

As far as I know no research exists to determine the reasons for bad writing, and I’m not sure how easy it would be to measure.

But Pinker might be right.

Because we all assume too easily that people know what we mean.

Shall I explain?

What is the curse of knowledge?

Have you ever had a conversation with an expert and wondered, What the hell are they talking about?

I still remember when I had just quit my job and spoke to an accountant about tax regulations and setting up my business. He talked about VAT software, thresholds, tax exemptions, filing dates, and he spoke in such general terms that I struggled to keep up and didn’t understand how his advice applied to my situation.

It’s called the curse of knowledge.

I used to think the curse of knowledge was something that happened to experts only. But in a way, as communicators, we all act as experts. We have ideas we want to share, and we know something about those ideas that our readers or listeners don’t know.

And that’s where ambiguity and misunderstandings sneak in.

It can happen to all of us.

What science says about the curse of knowledge

In their book Made to Stick, Chip and Dan Heath describe a study in 1990 by Elizabeth Newton.

Newton divided people into tappers and listeners. The tappers would tap out a song and the listeners would have to guess what song it was. This research earned her a PhD in psychology at Stanford University.

After tapping a song, the tappers were asked how many of the listeners would guess the song right. The tappers were moderately confident. They thought that one in two songs would be guessed correctly.

The truth?

Only 1 in 40 songs was guessed correctly.

As writers and speakers, we’re all tappers. We’re all overly confident that we’ll get our message across. But the truth is that we often fail.

Why is this?

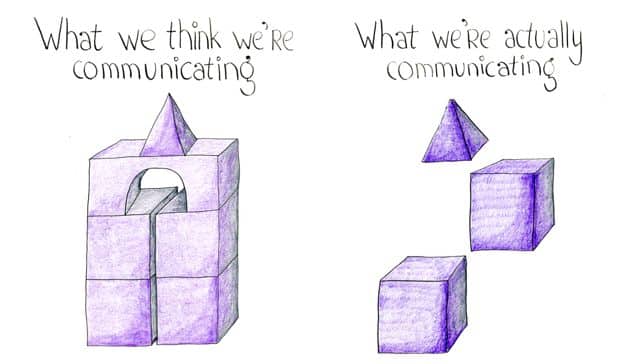

The tappers knew what song they were tapping. While tapping, they were hearing the words of the songs in their mind, so it seemed obvious to them which song it was. But to listeners, it wasn’t that obvious. They could only hear the tapping—not the words the tappers were hearing in their minds.

As communicators, we’re often overly confident that listeners and readers will know what we mean. But our messages may be hidden between the lines.

How to avoid the curse of knowledge

1. Get feedback

The first way to avoid the curse of knowledge is to keep communicating with your audience and encourage feedback.

I love it when I get questions about a blog post. Sometimes, I left gaps in my communication. At other times, a reader has thought through a problem better than me.

2. Use plain language

To avoid the curse of knowledge, it’s a good idea to avoid gobbledygook and use plain language instead.

For instance, in an article on the benefits of analogies, The School of Life explains what an analogy is and gives examples:

Analogy works by picking out a feature that is clear and obvious in one area and importing it into another field that happens to be more confusing and intangible. Take the analogical phrase ‘papering over the cracks’ – commonly used to suggest a shoddy, incomplete, lazy or dishonest manoeuvre. It is easy to develop a vivid image in our minds of how putting up wallpaper can hide multiple defects in plasterwork. But it might be much harder to see that, in a relationship, going on an expensive holiday won’t do anything to address the daily conflicts of life together or that, at work, moving to fancy offices won’t alter the deep problems with the quality of the management team.

3. Revise and edit

Leaving a draft for one or more days can help you see the gaps in your writing. Read your draft slowly and try not to read between the lines. What’s actually written? What does each sentence communicate? And what’s missing?

4. Use concrete examples

My favorite way to lift the curse of knowledge is to use concrete examples and stories to illustrate ideas …

A fab example of clear communication

Here’s a challenge for you …

How would you explain the idea of socioeconomic unfairness?

Socioeconomic unfairness means that it’s expensive to be poor. When you don’t have much money, you can only buy lower quality products at a lower price but such products don’t last very long. So you have to replace them more quickly.

Still a bit vague?

In the fantasy novel Men at Arms by Terry Pratchett, Captain Samuel Vines gives a fab explanation of socioeconomic unfairness:

Take boots, for example. He earned thirty-eight dollars a month plus allowances. A really good pair of leather boots cost fifty dollars. But an affordable pair of boots, which were sort of okay for a season or two and then leaked like hell when the cardboard gave out, cost about ten dollars. (…)

But the thing was that good boots lasted for years and years. A man who could afford fifty dollars had a pair of boots that’d still be keeping his feet dry in ten years’ time, while a poor man who could only afford cheap boots would have spent a hundred dollars on boots in the same time and would still have wet feet.

Isn’t that a splendid way to explain why it’s expensive to be poor?

It works so well because it reads like a story, we can visualize the poor man spending money each year on a new pair of affordable boots and still having wet feet. In ten years, the rich man pays 50 dollars while the poor man pays 100 dollars for inferior boots.

The story is concrete. It’s about boots. But even though the example only mentions boots, we can easily imagine that similar calculations works for other items, too, like clothing, furniture, or household appliances.

To make your ideas clear to anyone, use concrete examples. It’ll make your writing more entertaining, too.

The curse of knowledge turns up everywhere

The curse of knowledge can strike at any time for any type of writing.

When writing a how-to blog post or any other instructions, we may skip a step or two because they seem obvious to us. But these steps might not be obvious to our readers.

And when writing a sales page, we may forget to translate features into benefits because the benefits seem obvious to us.

However, the benefits may not be obvious to your readers. For instance:

This bike has 24 gears, disc brakes, and an ergonomic saddle.

Much clearer text with benefits:

This bike has 24 gears, so whether you go uphill, downhill, or cycling on a flat surface you’ll be able to find the right gear. The disc brakes are safe and will break well, even when it rains and when roads get muddy. And you won’t get a sore bum because the ergonomic saddle remains comfortable after hours of cycling.

When explaining a concept or idea, you may be inclined to keep your explanation concise.

But conciseness is a curse if your explanation remains abstract.

Let’s lift the curse of knowledge

To write with more clarity, it’s best to assume our readers know nothing.

That doesn’t mean we dumb our writing down. It means that we don’t skip any steps, we avoid complicated language, and we explain abstract concepts with concrete examples.

And even when we’re careful to explain each step clearly, we don’t adopt a condescending tone.

Because we also assume our reader is as smart as we are, perhaps even smarter.

Happy writing!

Books mentioned in this post:

- The Sense of Style by Steven Pinker

- Made to Stick by Chip and Dan Heath

- Men at Arms by Terry Pratchett

Recommended reading on the curse of knowledge:

How to write clearly: A simple 4-step method

Abstract vs concrete language: How to tell better stories

The Zoom-In-Zoom-Out technique for better explanations

Hi Henneke,

It was a great read! I think you are right. Sometimes, when I re-read my work, I notice that the point is not clear. I get lost in describing an experience, and I just miss the point completely. I am trying to work on this by getting feedback from my loved ones and friends and it has helped me a lot. I also let my work sit out and re-read it to ensure quality and readability. Thanks for highlighting this, it has been a great read!

I think it’s one of the hardest things in writing. It’s so easy to assume that our message will be clear to our readers. It takes a lot of effort to avoid the curse of knowledge.

Thank you for the helpful post and your advice, Henneke. I usually have grammar mistakes in what I write, but that’s usually due to Autocorrect. Regards

I was going to reply to your comment that mistakes are human—we all make them. But as you suggest, mistakes can also be due to dodgy software.

I love the way you bring out your points: simple and at the same time solid. Plus, the flow is flawless. If you could understand Swahili language I could have told you ” kazi safi kabisa”

Thank you for your compliment, Deniz. I checked out the translation of “kazi safi kabisa” and Google Translate suggests “completely clean work.” I guess it suggests the reading is smooth without any stumbling blocks?

Yeah, exactly. 100% polished. Perfect job, Henneke👏

Thank you, Deniz 😊

Yeah, exactly. Perfectly polished with each sentence leading to another. I’m looking forward to being a great writer like you.

Such a powerful article. The curse of knowledge!!! What a thought and so well-drafted in words. I think we really miss these important points in life. Thanks for sharing this article. It is really very helpful.

I’m glad you found it useful, Sona. Happy writing!

Right. The curse of knowledge is the cause, and also the failure to empathise. (Plus bad technique ;-)) I always try to remember how I explained things to my kids. I had endless patience with them, so why not with my readers?

The best example of non-empatising-curse-of-knowledge-spreaders are most programmers 😉

I guess the difference is that kids tell us when they don’t understand it or have follow-up questions. But our readers aren’t always so forthcoming. They might just click away when our writing feels too difficult to understand (or too boring!).

I agree with you that it’s a failure to empathize plus bad writing technique. Perhaps, good writing skills can sometimes rescue us, even when we struggle to imagine or remember what it was like to be a beginner.

Thank you for another clear post with great advice. The features vs benefits section is something many people miss – and it is so important whatever you’re writing or selling. You could do a whole post on that!

That’s so true. So many people forget to translate features into benefits.

I actually wrote a blog post about features and benefits a few years ago: https://www.enchantingmarketing.com/features-and-benefits/

Hi Henneke,

I love Steven Pinker’s book. It’s the best book I’ve read on how to write clear, simple english. Keep up the good work Henneke.

Kind regards,

John

So far, I’ve enjoyed Pinker’s book, too. I haven’t finished it yet!

Thank you for stopping by John. I appreciate it.

Thank you ! Fantastic advice as always ! Love getting your emails 🥰

Thank you, Clare. I appreciate your compliment. Happy writing!

Well, you don’t seem afflicted by the curse of knowledge Henneke!! Well written. I first understood this when I started teaching. My husband would often point out that I did not explain many things because I assumed that the students knew. I realised that I had to teach to the level of the weakest student in the class and the rest would take care of itself.

Yet to decide that level during writing. But definitely working towards it. Thanks for this timely post.

I love that idea of teaching to the level of the weakest student. Thank you for sharing, Shweta!

“I love it when I get questions about a blog post.”

So do I, Henneke. Questions mean so much–may even raise profits.

Questions show understanding and can add to my understanding of my own topic, via concepts I did not think to consider or points of view that escaped me.

Questions add understanding to the reader/listener, if I can see a need to edit or add to my writing or oral presentation.

And questions show I have engaged the reader/listener to the point of desiring truly to learn the rest, to add completion to the parts that flew past my realization.

That’s why I often reply with the first words, “Great question! I’m so glad you asked that!” Even if the concept is something all people know, the asker may need only to be sure of my intention.

Clarity. Clarity is the amazing equalizer that, at the same time, is uplifting. Like a rising tide.

I love that: Clarity is uplifting. It’s so true.

I love your attitude to questions. I, too, have learned so much from people asking questions (here in the comment section, by email, and in my courses). The questions make me a better teacher. It’s always the “fault” of the teacher / communicator when the message is unclear.

I love this post. It gets right to the point. Thank you for practicing what you preach. Though we’ve never met, I consider you my writing coach.

Thank you, Wally. It’s an honor to be considered your writing coach.

Hi Henneke,

Thanks so much for continuing to write on your blog. I think yours is the only one I still read from the hundred I signed up for years ago!

I agree with your article. The curse of knowledge exists everywhere, from marketers to doctors. But I’d like to add a thought.

I wonder if people tend to write too generally because they fear they might offend their readers? Nobody likes to seem like a “know-it-all” and tell people something they already know. So if in my mind something seems obvious and I think that someone else will also think it’s obvious, the fear of offending (or perhaps fear of rejection on a deeper level) speaks so loudly that I omit important details.

Getting good at communication, both spoken and written, is truly a lifelong journey. Thank you for writing. You force me to reflect on my own writing (and my fears) which makes me a better communicator.

Best,

Eric

Thank you, Eric. It’s an honor that you’re continuing to read my blog. That means a lot to me!

And you make an excellent point. I agree there’s an issue of writers being afraid of dumbing down their texts. The way I get around it is to think that the examples I use should be so good that even experts still enjoy reading my articles.

I also think it’s a question of tone. You can sense it when a writer thinks her readers are less smart than the writer herself (or as she smart as she thinks she is). A condescending tone can also sneak in when we forget to think of our readers as human beings just like us. When you address a faceless crowd, it’s easy to belittle the crowd.

When you think of your readers as your friends with whom you’re drinking a cup of tea together, the tone instantly becomes different.

If writing is good enough, we don’t need to be afraid of offending or dumbing down.

Henneke

Love the simplicity of your writing. You have practically proved what you are saying in the boot story. At the end you showed clearly the difference between giving just fact about the cycle parts and then their importance. Brilliant stuff. Very helpful tips for a beginner like me. thank you very much posting this.

Thank you for your compliment, Premashantha. I’m glad you found this useful. Happy writing!

Hi Henneke, I could relate to your accountant, I had the same experience last week. I did not understand one thing they said in an email to me. I replied and still haven’t heard back. They probably don’t know any other language to explain it in.

Loved your boot story, that really explains the context in a nutshell!

Excellent points as usual Henneke, thank you!

I’m glad I’m not the only one who’s struggled to follow an accountant!

Thank you for stopping by, Lisa.